Re-mythologizing Myths and Fairy Tales in Margaret Atwood’s Surfacing

Carla Scarano D’Antonio

‘This above all, to refuse to be a victim’

Surfacing

A quest of personal and national identity is at the core of Margaret Atwood’s novel Surfacing, published in 1972. The unnamed protagonist is engaged in an individual and nationwide search on the verge of insanity trying to reconstruct her split self. This is highlighted in the course of the narration through an exploration of new myths and symbols that encompass native cultural values whilst exposing the dated quality of classical stories which need to be adapted and integrated in the context of the Canadian society. It is an attempt to re-write the narratives and give space to alternative perspectives from the point of view of marginalized categories, such as women and natives. Furthermore, it goes together with an essay to blur oppositional dualities such as nature/city, wilderness/civilization, coloniser/colonised, victim/victimiser, in view of an alternative inclusive vision that implies transformation and acceptance of multiplicity.

The protagonist of the novel goes back to the island in Quebec where she grew up in search of her father who had mysteriously disappeared. Her partner Joe and another couple, David and Anna, are with her. During the narration she reconstructs her past from memory revealing the traumatic experience she had when she moved from the wild and isolated life with her family on the island to the city where she attended an art course. Reviewing her life, she needs to acknowledge her complicity in the role of victim in the fabricated story of her marriage, divorce and abandonment of her child. This is subsequently declared to have been a love affair with her married art teacher who persuaded her to have an abortion. The consequences of her fragmented psychological condition influence her capacity for feeling and relating to others which brings her to seek alternative possible narratives in order to attain wholeness at personal, cultural, national and linguistic levels.

In the novel Atwood underlines the value of finding new narratives that refer to Canadian folk tales, such as the Indian stories of the Wendigo and Wabeno and the Quebecois stories of Loup-Garou. She also explores the Canadian version of the Grimm Brothers’ fairy-tales, especially ‘The Golden Phoenix’, ‘The Fountain of Youth’, ‘The Juniper Tree’, ‘The White Snake’, ‘Fitcher’s Bird’, ‘The Girl without Hands’, and the myths of the Triple Goddess, Callisto and the Demeter-Persephone duality.

Hendrick Goltzius, Diana Discovers Callisto’s Pregnancy (1599). Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht.

The fairy tales’ intertext underlines the limited quality of this mythical past, parodied by the drawings the protagonist produces for the anthology of The Quebec Folktales she needs to illustrate. The Golden Phoenix, symbol of death and rebirth, the eternal power of creativity, is represented as ‘a fire insurance trademark’ and later reinterpreted as a ‘mummified parrot’; the princess ‘looks stupefied’ with ‘one breast bigger than the other’ and the Giant guarding the fountain of life looks like a ‘football player’. The evoked fairy tales, purged of the loup-garou stories and of the colour red, highlight the debased and constrained roles the protagonist expresses in her drawings. They expose the void quality of these roles that need to be reinterpreted, as she claims that ‘[t]he Fountain of Youth and The Castle of the Seven Splendours don’t belong here’.

The loup-garou is evoked in the narration with references to the protagonist’s father she imagines hidden in the forest and transformed into a wolf. In her Gothic fantasy she visualizes herself trapped on the island and wishes to protect her friends from his possible attacks. The father she is looking for and consciously depicts as her guide and source of knowledge is therefore unconsciously represented as a fearsome, ferocious beast. The fairy tales’ narratives are useless for the protagonist’s quest, so their essential meaning needs to be re-created, re-mythologized, transformed from within to maintain its significance and power. She needs to look for different stories of ‘bewitched dogs and malevolent trees’, Canadian stories linked to the land and to the wild. Significantly, the third princess she paints ‘gets out of control’ on the wet paper as she adds ‘fangs and a moustache, surrounding her with moons and fish and a wolf’. This is an attempt to create an alternative to the invalidated stereotypes of the classic fairy tales, connecting instead with the narratives of the wilderness and the stories of the natives.

In her attempt to reconstruct her split self, the story of ‘The Girl without Hands’ is disturbingly evoked as well. She feels amputated by her fantasised divorce and delivery. However, the most significant amputation she has experienced has been suffered in terms of her creativity. Her teacher-lover diminished her talent and induced her to choose the commercial artist role ‘because there have never been any important women artists’. He gives her low grades and keeps her separate from his family life. She worships him like a god, in the same way she considered her father a god, but he was no god, only an average man who took advantage of her. Moreover, the father himself forced them to live on the island ‘split … between two anonymities, the city and the bush’, and she finds his ‘crude drawing of a hand … More hands’ to signify the castrating quality of her father’s role in her life which she unconsciously evokes.

The search for wholeness necessarily passes through the re-appropriation of the relationship with her mother, a rediscovery of her repressed self, and her mother’s powers, which she needs to acknowledge. She negates these powers at the beginning both because she privileges her father, who represents the symbolic rational function that entraps her and creates false myths, and because her mother was silenced and mute: her diary only records the weather and the last pages are blank. The mother is diminished like the daughter. She leaves the protagonist only a drab leather jacket, references to which recur in the narration, with no apparent clues, a silent presence. In contrast, her father left maps and drawings, which eventually reveal themselves as a partial and incomplete guide. Inside the leather jacket are insignificant remnants that stress even more the belittled aspect of her mother’s life. The husks of sunflower seeds in the pockets of the jacket accentuate the hollowness of the woman’s place in society and they recall the pomegranate seeds Persephone eats before returning from the underworld to see again her mother Demeter. The myth is re-mythologized as the pomegranate seeds, symbol of fertility and rebirth, are transformed into hollow sunflower husks to expose the absence of transcendence and the need to fill the narratives with stories that integrate old and new myths.

Hades abducting Persephone, painter unknown (eighteenth century).

The intertexts of the Demeter-Persephone myth and of the myth of the Triple Goddess underline the potential power inherent in the maternal heritage as well as the necessity to accept the dark side of the triad (Hecate) and the frightening, painful descent into the underworld of the unconscious. The recollection of her mother’s relation with the animals is a reinterpretation of the fairy tale of ‘The White Snake’, where this time it is a woman not a man who has the power to speak with the animals, which underlines the authority of her mother’s capacities. She is the new mythmaker, the one who can perpetuate the power of storytelling and language, who can guide her to rebirth. But she is also aware of female powerlessness in a male world, where women break their ankles in an attempt to fly, as she did when she was a girl.

The return of Persephone, Attic Red Figure Krater, ca. 440 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York).

The wilderness is ‘a place of regeneration’ as Howells (2005) claims, where the protagonist is dynamically transformed after her descent into the underworld of the unconscious, symbolized by her immersion in the lake where she finally finds the body of her father and becomes aware of the abortion. Distinct from the Callisto myth, the protagonist of Surfacing voluntarily exiles herself from a society that has failed her. The wilderness is a chosen shelter and a possible alternative to the destructive consumerist and imperialist society of the city. It is a place that allows her to reconstruct her split self through a metamorphosis where she merges with the landscape, regressing to the animal stage. She eschews all the products of civilization and temporarily lives in the forest in order to open herself to new myths. These are symbolized by the stone paintings traced in her father’s maps which she discovers in her immersion in the lake. Significantly, the pictographs are red, a sacred colour for the Indians, important discoveries copied by her scientific father as a retirement hobby. Their language is similar to the protagonist’s professional language, which is based on illustration and which, therefore, allows for an alternative mythical representation. In this way she opts for and explores a pre-historic native past that she feels to be more authentic than the fabricated present of the civilized world. She wraps herself in a blanket, waiting for a fur to grow on her body, eats plants and berries and refuses speech. She feels transformed into a tree, into a place, a process that is a breakdown but also a breakthrough. This allows her a renewed vision where she acknowledges her complicity in being a victim and decides to become ‘a creative non-victim’.

Crispijn van de Passe, Arcas Shoots Callisto (1602-1607). Rijksmuseum.

In her attempts to re-write the myths she not only needs to acknowledge her complicity in the victim role and her refusal to be a victim, she also needs to accept her dark side (Hecate) as she realizes that humans are not gods and can be both good and bad. Her sexual intercourse with her partner Joe fills her maternal hollow husks with a possible pregnancy but also implies the impossibility of surviving in total wilderness, in a state of constant rejection, which would be fatal. Nevertheless, her interpretation of the world is now multiple, inclusive and acknowledged as such: ‘From the lake a fish jumps/An idea of a fish jumps’; it can take many shapes and become ‘an ordinary fish again’.

This return to ordinariness after the frightening experience of the underworld, culminating in the apparition of the ghosts of her parents, implies a renunciation of the total wilderness. It is an acknowledgement that the gods she has evoked cannot help her in the end and it is a declaration of the absence of transcendence: ‘they’re questionable once more, theoretical as Jesus’. This brings her back to the necessity of compromising with language and civilization. She may have acquired self-knowledge in the descent into the underworld, in her woman’s heroic journey in the darkness of her frightening traumatized unconscious, but she has to return to a world that has not changed, that is hostile to women. In her decision not to be a victim she is aware that she needs constantly to re-negotiate her position with her partner Joe, returning to a world where women cannot fly. It is a world where abortion is a crime and where a single mother is an outcast.

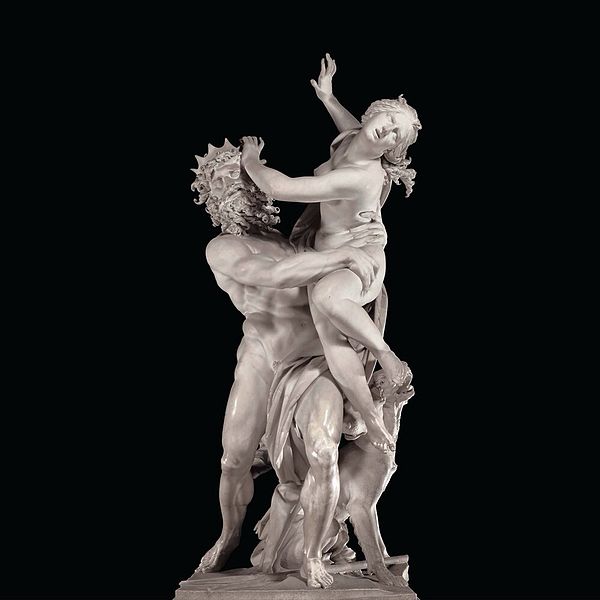

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, The Rape of Proserpina (1621-22). Galleria Borghese, Rome.

In a world of language where myths are neither transcendental nor eternal, but nevertheless are powerful and influence personal and collective narratives, Atwood proposes possible alternatives by demonstrating that traditional discourses need to be re-mythologized and re-written from different points of view including marginalized categories. They are a product of human history and are able to adapt to the circumstances of the society in which they appear.

At the end of the novel the protagonist decides to trust Joe, but the process will be slow and difficult, an incessant mobility, as the gerund in the title of the novel highlights. The woman needs to find the Golden Phoenix inside herself connecting with the frightening and redemptive maternal power in order to be a creative non-victim. The gods are absent, ‘asking and giving nothing’.

References

Margaret Atwood’s works:

- Surfacing (London: Virago Press, 1979, 2002)

- The Journals of Susanna Moodie (London: Oxford University Press, 1997)

- Procedures for Underground (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1970)

- Conversations (London: Virago Press, 1992)

- Survival: A thematic guide to Canadian Literature (Toronto: Anansi Press, 2012)

- Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995)

Essential bibliography:

- Appleton, Sarah A., ed., Once Upon a Time: Myth, Fairy Tales and Legends in Margaret Atwood’s Writings (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2008)

- Grace, Sherrill, Violent Duality: A Study of Margaret Atwood (Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1980)

- Hill Rigney, Barbara, Women Writers. Margaret Atwood (Basingstoke: Macmillan Education, 1987)

- Howells, Coral Ann, Margaret Atwood (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005)

- Lauter, Estella, ‘Margaret Atwood: re-mythologizing Circe’ in Estella Lauter, Women as Mythmakers: Poetry and visual art by twentieth-century women (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984)

- Wall, Kathleen, The Callisto Myth from Ovid to Atwood. Initiation and rape in literature (Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988)

- Wilson, Sharon Rose, Margaret Atwood’s Fairy-Tale Sexual Politics (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1993)

- Wisker, Gina, Margaret Atwood: an introduction to critical views of her fiction (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)

This research is funded by the Canada-UK Foundation.

Carla Scarano D’Antonio obtained her MA in Creative Writing at Lancaster University and is working on a PhD on Margaret Atwood at the university of Reading. She and Keith Lander won the first prize of the Dryden Translation Competition 2016 with translations of Eugenio Montale’s poems.

Great article Carla. I read and was fascinated by ‘Surfacing’ when it first came out on the 70s. Illuminating to read in conjunction with Atwood’s autobiographical writing and her Selected Poems, 1965-75, too.

Thank you Alex, I am glad you enjoyed it.

Pingback: What happened at our January meeting – news and readings – Woking Writers Circle